Renal Cancer

Renal cancers are responsible for roughly 3% of all adult neoplasms, being the third urologic cancers in frequency, only less common than prostate and bladder cancers. Renal cancers are, however, the most aggressive of all urologic tumours. In fact, renal cancers are a very heterogeneous group of tumours regarding histology and biological behaviour, with variable and unpredictable responses to both local and systemic therapies; 90% are clear cell carcinomas. Incidence varies globally, but is larger in occidental countries. In the last decades, there has been a small but steady increase in its incidence. Mortality rates remain stable, but there was a decrease in mortality rates in some countries. It is more common in men than in women (2:1), with a mean age at diagnosis of 64 years. Nowadays, more than 60% of all renal cancers are localized at diagnosis, being more often asymptomatic. Most cancers are incidentally diagnosed, due to the widespread availability of image exams such as ultrasound and computerized tomography, often ordered by family physicians or clinicians during routine check-ups or during emergency room visits. Most often, tumours are single, and restricted to one kidney; however, roughly 3% of cases are bilateral and 10% are multi-centric.

Are there strategies for prevention?

Nowadays, there are no absolute means to avoid the development of renal cancers, since we do not understand completely its aetiology.

Is it possible to reduce the risks of developing a renal cancer?

Multiple factors potentiate the risks of developing renal cancers. These risk factors imply a higher probability, but in no situation can we affirm that they will result in the occurrence of the disease. Many of the risk factors for renal cancers are modifiable, dependant of our lifestyle. Other factors, such as genetic predispositions and hereditary factors are impossible to modify.

Modifiable risk factors for renal cancer

Smoking

Smoking increases the risk of developing renal cancer, and is related to the amount of tobacco consumed. Former smokers also have a 25% increase in the risk of renal cancer, but after ten years of smoking cessation the risk returns to the baseline risk of non-smokers.

Obesity

Diet-related factors, such as increased fat consumption and obesity increase the risks of renal cancer. Hormonal changes secondary to an increased body mass index raises the levels of insulin and estrogen, and causes changes in cholesterol metabolism and immune function, which lead to and increased risk of renal cancer.

Exposure to metals and chemical products

Many studies confirmed the association between renal cancer and occupational and home chemicals such as Cadmium, herbicides and organic solvents. Trichloroethylene, which is used to remove fat from metals and is present in adhesives and ink and stain removers.

Non-modifiable (genetic and hereditary) risk factors

Some individuals inherit deficient genes that increase the risk of renal cancer and other diseases. Cancers resulting from these genes are named familial or hereditary cancers. The correct identification of such genes may help in the early recognition and treatment of patients with these diseases. Hereditary renal cancers are more prone to be bilateral and multi-centric; they also tend to occur earlier in the life of individuals. Therefore, patients with propensity to develop hereditary cancers should be tested more often with tests such as ultrasound examinations. It is known that less than 10% of renal cancers are hereditary, and that the history of risk factors does not necessarily incurs in the development of renal cancer. However, patients with a family history of renal cancer or of associated diseases may benefit from genetic counselling.

Von Hippel-lindau’s disease

This disease, caused by a mutation in von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) gene, is related to an increased risk of developing various neoplasms throughout the body, especially renal cell carcinomas.

Tuberous Sclerosis

Another example of a disease caused by a deficient gene, one of every three cases of tuberous sclerosis is hereditary. It is associated with an increased risk of developing renal neoplasms, in addition to cutaneous, cardiac and cerebral problems.

Hereditary Renal Papillary Carcinoma

Generally associated with mutations of the MET gene, this disease favours the development of single or multiple papillary carcinomas of the kidney.

Renal Carcinoma associated to hereditary Leyomiomatosis

Patients with this syndrome may develop smooth muscle tumours called leyomiomas (fibromas) of the uterus and skin, and are at an increased risk for papillary renal carcinomas, usually related to mutations in the gene of the enzyme fumarate hydratase (FH).

Birt-hogg-dube’s (BHD) Syndrome

Patients with this syndrome develop small benign skin tumours, in addition to an increased risk of developing renal cancers. The gene altered in this syndrome is FLCN.

Familial Renal Cancer

Patients with this syndrome develop paragangliomas in the head, neck, adrenals and other sites. They also tend to develop bilateral renal cancers early in life, often before age 40.

Other risk factors

Family history of renal cancer

Individuals with a first-degree relative (father, mother, brothers, sisters, sons or daughters) with a history of renal cancer are up to two times more likely to develop renal cancer. It is unknown whether this is due to genetic factors, environmental factors, or both.

Hypertension (increased blood pressure)

Some studies have found a positive correlation between high blood pressure and renal cancer. This probably has more to do with the disease itself that to ant-hypertensive treatments.

Medications

PHENACETIN:

An analgesic associated to the development of renal cancer. It has been discontinued for years now, and is not an important risk factor anymore.

DIURETICS:

Some studies have found a small but significant correlation of the use of diuretics and the risk of renal cancer. It is uncertain if this is due to the disease itself or to the medications.

Advanced renal disease

Patients in dialysis for the treatment of chronic renal insufficiency present an increased risk of developing renal cell carcinomas.

Race

African descendants, American Indians, and Alaska natives have a slightly higher risk of renal cell carcinomas than Caucasians.

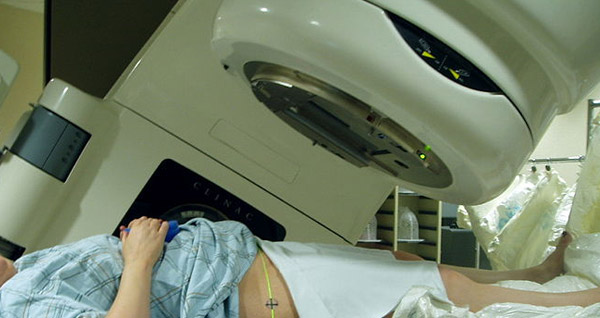

Radiotherapy

Men with a history of radiotherapy for the treatment of testicular cancers and women with a history of radiotherapy for the treatment of uterine cancers have twice the risk of developing renal cancer.

Histology

Roughly 70% or renal cancers are clear cell carcinomas. Papillary carcinomas are second in frequency (around 10%), and the ones most likely to be bilateral, having also a less aggressive behaviour than clear cell carcinomas. Chromophobe tumours represent 5% of cases, and are less aggressive. Any of the histologic types may undergo sarcomatoid transformation, which is related to a more aggressive behaviour and more ominous prognosis.

How renal cancers are diagnosed?

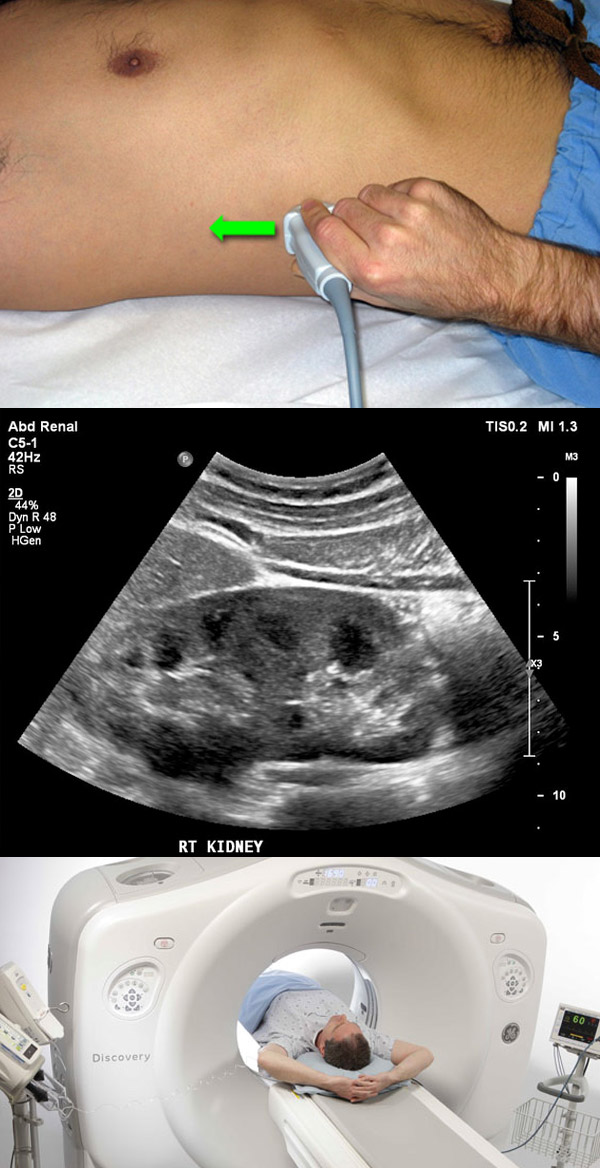

Renal cancers are called the “internist tumour” due to the wide variety of presenting signs and symptoms produced. However, more recently most renal cancers are being diagnosed incidentally, due to the widespread utilization of imaging studies such as ultrasound, computerized tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging in clinical medicine. Most incidentally diagnosed tumours are small, clinically localized, and have not produced symptoms when diagnosed. When symptoms do exist, the most common is haematuria (blood in the urine), which is usually asymptomatic and may be visible, with the elimination of blood clots in the urine.

Other possible signs and symptoms are:

- Lumbar or flak pain.

- Palpable abdominal or flank mass.

In more advanced phases of the disease:

- Fatigue.

- Loss of appetite.

- Weight loss.

- Edema of the lower limbs.

- Bone pain.

- Acute varicocele.

Although less common, “paraneoplastic” signs and symptoms may occur:

- Arterial hypertension.

- Fever.

- Anemia or policytemia (increase in red blood cell count).

- Hypercalcemia.

- Liver dysfunction (Stauffer’s syndrome).

Imaging

Imaging studies have for long now been the mainstay of the diagnosis of renal cancers. Ultrasound can reliably differentiate between cystic and solid lesions, although it cannot ascertain whether tumours are hypervascular or if there are intravascular thrombi. Computerized tomography (CT) is the preferred imaging study for the diagnosis and staging of renal cancers. It allows for the adequate characterization of cystic lesions, with the identification of septs or solid nodules in complex cysts. It also determines the degree of vascularization of the lesion and the presence or not of intra-lesional fat (commonly seen in benign tumours).

Furthermore, it is useful to the surgical planning by detailing tumour location and vascular supply. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is more useful than CT in determining tumour invasion of the renal vein and cava, and is the exam of choice when the patient is allergic to CT contrast or during pregnancy. It is also commonly ordered in cases in which CT is not conclusive. Positron emission tomography (PET-CT) is used mostly in cases of local recurrence or in the evaluation of metastases in situations in which conventional imaging is doubtful. It is not utilized for the diagnosis of primary lesions.

Bone scans are indicated in the staging of high-risk tumours (large tumours, enlarged regional lymph nodes) or in patients with bone pain.

Treatment

Treatment varies according to factors such as disease staging and comorbidities of the patient, patient-s performance status, general health and the presence or absence of symptoms.

The therapeutic options for the primary lesion are:

- Surgery: radical or partial nephrectomy.

- Ablative therapies: cryotherapy and radiofrequency.

Nephrectomy, either radical or partial, is still the most effective treatment for renal cancer. The aim is the complete (margins free) removal of the tumour. It may be performed open, laparoscopic, or robot-assisted. Oncologic results are the same between techniques, although the minimally invasive approaches (laparoscopic and robot-assisted) usually result in less postoperative pain, better cosmetic results and earlier hospital discharge. Partial nephrectomies are the main choice for tumours of 4 cm or less, and an option for lesions up to 7 cm. The main advantage of a partial nephrectomy is the greater preservation of functioning renal parenchyma. Laparoscopic nephrectomies are performed through small 5 to 12 mm incisions (3 to 5 ports) through which surgical instruments are introduced. One of the ports is to introduce the optical system, which connected to a video camera allows the surgeon to perform the surgery with magnified and high definition vision. At the end of the surgery, one of the ports is augmented in order to remove the tumour or the whole kidney. In robot-assisted nephrectomies, a robotic interface (da Vinci) allows for the surgeon to remain seated in a console placed next to the surgical table, controlling the robotic arms in order to perform the surgery. For the surgeon, the robotic system offers a greater freedom of movements and precision as compared with conventional laparoscopy. Nevertheless, it is the experience and dexterity of the surgeon that determine the result of the surgery, more than the technique employed. In the case of very small tumours in patients with advanced age or comorbidities, multi-centric or bilateral tumours, there is the possibility of ablative treatments such as cryotherapy (freezing of the tumour) or radiofrequency (necrosis of the tumour by radiofrequency waves). In some selected cases, surveillance may be an option, since small tumours usually are slow growing and have a long and protracted clinical course, with a low probability of metastasizing. In the cases in which there are metastases, there is the option of metastasectomies in selected cases or systemic treatments:

- Target-therapies.

Conventional radiotherapy and chemotherapy are not effective in the treatment of metastatic renal cancer, and are limited to palliative and analgesic care. In deciding which local or systemic treatment is the best for an individual patient, one must consider the risks and benefits, since many treatments include a substantial morbidity, sometimes with limited gains.

How do we follow a patient with renal cancer after initial treatment?

After treating the primary lesion through surgery or ablation, the patient should be followed according to the characteristics of the disease with exams that may include CTs, ultrasound, chest x-rays and bone scans. Follow-up varies according to the characteristics of the disease, generally for no less than 5 years. The aim of follow-up is to detect and to treat early recurrences of metastases, often with chances of cure.

What else can I do after the initial treatment of my renal cancer?

After the initial treatment, the patient may modify life harmful habits and adopt a healthier lifestyle. And what can we do to live healthier?

- Eat healthy meals

- Avoid alcohol

- Quit smoking

- Reduce stress

- Perform physical activities.

Eventually, patients who survived a cancer treatment may benefit from the input of friends, relatives, support groups and religious organizations.